When Stronger Presidential Powers Could Be Worth The Risks

Americans are wary of presidential power, yet simultaneously demand a “Green Lantern” president—one who can break through gridlock to enact their agenda. This tension is not new; it’s as old as the Republic itself. In The Federalist, No. 70, Alexander Hamilton raps:

“The ingredients which constitute energy in the executive, are, unity; duration; an adequate provision for its support; competent powers. The ingredients which constitute safety in the republican sense, are, a due dependence on the people; a due responsibility.”

In an era of congressional gridlock and partisan polarization, some scholars argue that the balance has tipped too far in the direction of safety. What we need is a more powerful presidency, one that can circumvent a parochial Congress to enact policies in the broad, national interest. In some cases, presidents, and presidential hopefuls, have heeded the call, proposing expansive unilateral agendas and promising to go over the heads of lawmakers on Day 1.

Of course, what you think about a president going over the heads of legislators to enact his agenda depends, in some sense, on your politics. As Justice Kagan makes clear:

“The desirability of such [presidential] leadership depends on its content; energy is beneficial when placed in the service of meritorious policies, threatening when associated with the opposite.” (2001, 2341)

Given the narrowness of presidential elections (to say nothing of the normative implications), how do we appropriately balance the desire for presidential action with the demands of democratic deliberation and control? Would it be better to further empower the president to enact policies in the national interest? Or is it better to play it safe, accepting some measure of legislative gridlock to prevent overly partisan or potentially damaging policies from taking effect when someone we oppose takes office?

To help understand these tradeoffs and consider the consequences of expanding presidential power, I develop a game-theoretic model in my 2021 article “Energy Versus Safety: Unilateral Action, Voter Welfare, and Executive Accountability,” which I summarize below (with no Greek letters!).

Setting It Up

The model takes place over two periods and features an executive, a legislator, and a voter. In each period, the politicians (i.e., the executive and legislator) are tasked with passing a policy, either Policy 1 or Policy − 1. After the first period, an election is held, and the voter reelects or replaces each politician.

The voter always prefers Policy 1, and he would like the politicians to enact it. However, politicians vary in their policy preferences. Congruent politicians prefer Policy 1, and divergent ones prefer Policy − 1. Although the politicians know each other’s types, the voter does not. He can only infer their types after observing what policy they enact. Politicians also value holding office and would like to get reelected. Thus, politicians may need to be strategic about their choice.

To answer my research question about the tradeoffs between energy and accountability, I consider two versions of this policymaking game, discussing what the politicians do and how the voter fares in both settings.

The Costs and Benefits of Checks and Balances

First, I consider a version of the model called Checks and Balances, where the politicians must agree on policy in order to pass it. In the first period, the legislator privately chooses a policy, 1 or − 1. Then, the executive sees which policy the legislator has chosen. If he ratifies that policy (also choosing 1), then that policy is enacted. If he rejects the policy (by choosing − 1) gridlock occurs and a status quo policy, 0, is implemented instead. The voter does not see the politicians actions, he only sees the end result—either new policy or gridlock and the status quo.

In the paper, I discuss a semi-separating equilibrium in which the voter reelects politicians when they pass policy 1 and replaces them both otherwise. Importantly, if the voter observes gridlock, he infers that the incumbents are more likely to be divergent than new politicians—even though gridlock only occurs when one politician is congruent and one is divergent. Given the joint policy signal, he has no way of knowing which is which.

Going It Alone

Next, I consider an alternative setting, Unilateralism, where, after the legislator privately chooses policy 1 or − 1, the executive can either play the same game described previously (approving or rejecting the selection), or instead, he can disregard the legislator’s choice and unilaterally implement either policy. However, acting unilaterally is both transparent and costly. First, the voter knows if the executive acted unilaterally, and thus, can perfectly infer his policy choice. Second, the executive must pay a private cost for acting unilaterally.1

If both politicians are congruent types, the executive can implement Policy 1 and win reelection without paying the cost for unilateral action. However, when a congruent executive is paired with a divergent legislator, he can overcome gridlock by paying a cost to implement policy 1 unilaterally. This move increases the executive’s policy payoff, but the transparency also helps him electorally. The voter sees that the executive has enacted Policy 1 unilaterally, which must mean that the legislator is not congruent. The voter doubly benefits—he gets his favorite policy and learns both politicians’ types, allowing him to make better voting decisions. Knowing all of this, a divergent legislator who values reelection may decide to offer Policy 1 in an effort to avoid being outed by unilateral action.

Of course, we might be especially worried about the reverse—when the executive is divergent and the legislator is congruent. Here, the executive can avoid gridlock to enact Policy − 1. However, transparency in this instance works against him. Yes, he can implement Policy − 1, but the voter will correctly infer his divergent type, replacing him with a new executive in the election. Thus, divergent types are often constrained by electoral consequences.

When is the Unilateral Executive Better?

One might suspect that the voter prefers the game that empowers the politician who shares his policy preferences: Checks and Balances when the legislator is more likely to be congruent and Unilateralism when the executive is more likely to be congruent. And indeed, that is what I find when one politician is much more likely to be congruent than the other. However, if both politicians are similarly likely to be congruent types, then the Unilateral game is always preferable, even when the legislator is more likely to be a congruent type than the executive.

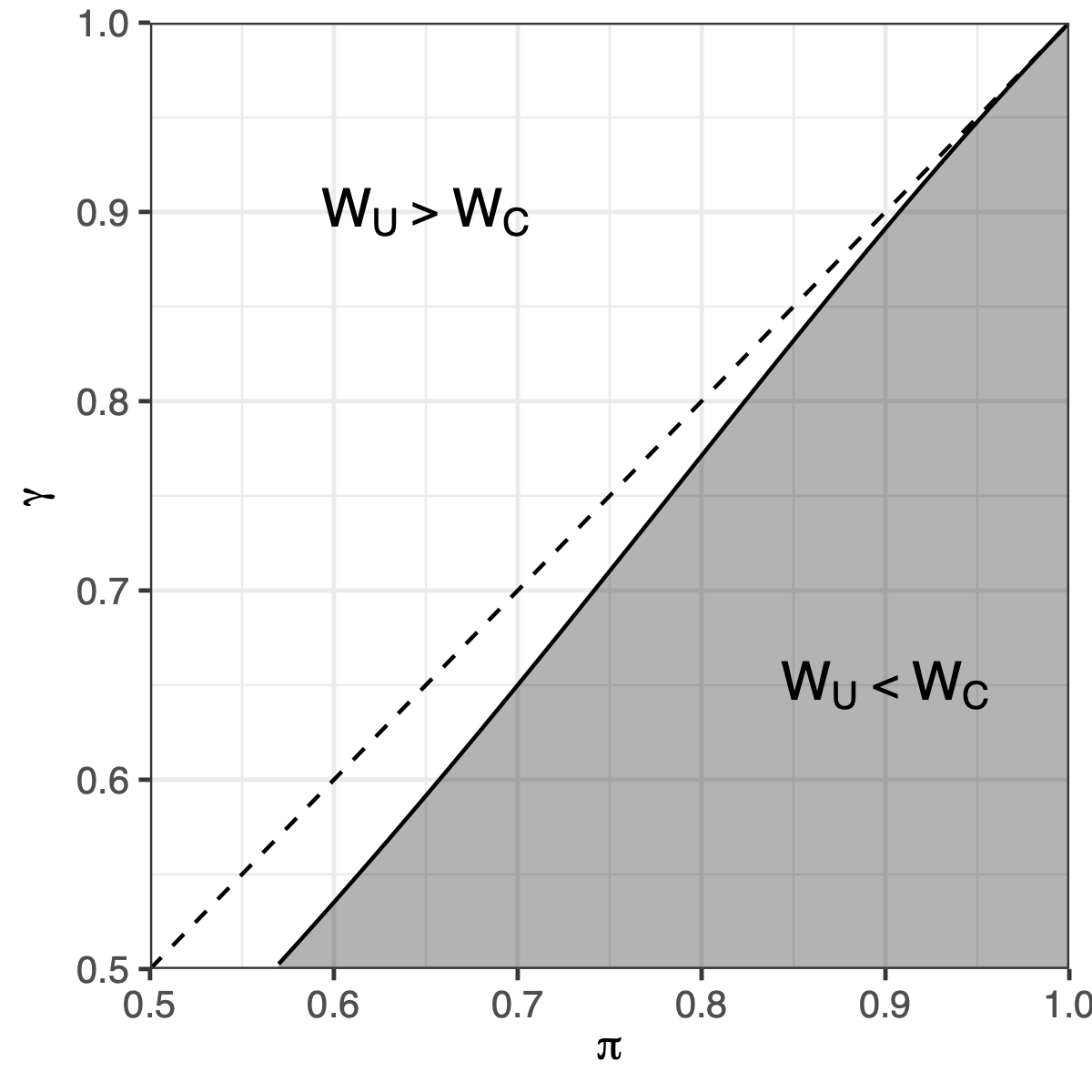

We can see this graphically in Figure 1 below. On the x-axis, I plot the probability the legislator will be a congruent type, and on the y-axis, I plot the probability the executive will be a congruent type. The solid line is every point where the voter is indifferent between either version of the game. The white area above the curve covers all prior probabilities of congruence at which the voter would prefer Unilateralism, and the shaded area below the curve represents all prior probabilities where the voter would prefer Checks and Balances. Finally, the dashed 45-degree line, represents a baseline case where the voter prefers the game that advantages the more-likely-congruent politician. Here, we see that the solid curve is always weakly below the 45-degree line (and the white region encompasses the 45-degree line). In this “wedge” area between the solid and dashed lines, the voter prefers Unilateralism even when the legislator is more likely to be a congruent type than the executive.

This wedge area is a result of the fact that (1) the congruent-type executive can overcome gridlock under Unilateralism to enact Policy 1, and (2) when he does, the voter learns valuable information about the politicians’ types. Although unilateral powers can be used to circumvent a congruent Congress, there are times the voter is willing to take that risk.

Concluding Thoughts

Americans are both skeptical of executive power and desirous of a strong leader who can tackle America’s growing challenges. Some scholars have argued that the solution is to further empower the president, however, these arguments often begin from the presumption that the president will have the “national interest” (rather than a partisan or personal interest) in mind. In this paper, I relax that assumption—allowing the executive to be either congruent or divergent, and reach a similar, but nuanced, conclusion (NB: one that assumes, rightly or wrongly, that the policies enacted do not subvert democratic elections). Although divergent executives may abuse their powers and enact policies that run counter to the voter’s interest, they may be constrained by the same forces that brought them into office in the first place: electoral politics.

This blog post is based on my 2021 article “Energy Versus Safety: Unilateral Action, Voter Welfare, and Executive Accountability” in Political Science Research and Methods.

This cost captures the bureaucratic resources needed to create an executive order as well as the potential for reversal by a future executive. ↩